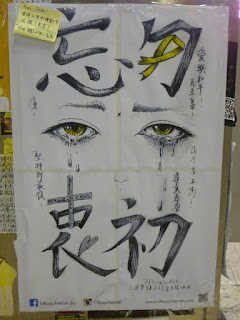

Don't Forget Your Original Conviction

Because of the dojo training schedule change, I got to listen to the radio Tuesday night and caught the tail end of the NPR show "HumanKind" that I never listened to before. It was the second half of a two-part series "Health Care With Kindness".

On the show, a nurse trainer is working on bringing kindness into the healthcare system. She recounted a personal experiences from the other side: a family member was hospitalized and she was there visiting. At regular intervals, medics come in the room to take the patient's vitals. They talk with a flat, distant voice. No eye contact with the patients or their families. They do what they need to do, and they are immediately on their way. Very transactional. A register nurse echoed the sentiment by admitting that she and her peer were trained to behave the same way. Be detached and impersonal. Kindness and compassion were not part of the equation.

"Were you trained to never cry with your patients?" the host asked. "Yes, we were. However, I cannot say that I followed that strictly." She went on to describe how one time she cried with her patient.

At the ER, a trauma patient was bleeding so extensively that, after trying for a while, the medical team decided that there was nothing more they could do to save him. One after another, they left the room. The patient, who was still conscious, gathered that the doctors had given up on him and that he was dying. "Am I dying?" he looked up to seek confirmation from this nurse. She did not answer the questions. Instead, she said, "I am here with you." Tears came down her cheeks as she held the patients hand with hers.

I told my chiropractor about the radio show. His face dropped as I got to the point about kindness being non-existent in the healthcare system. "Nope, it is not about the people. What kindness? They don't know about kindness. It's all about the money." Then I noticed my doctor was tearing up.

"Do you know that I once almost died?"

My doctor told me he had a very bad case of asthma as a child. He was hospitalized. His doctors thought he might not make it. It was 1955. Prednisone just came out. His mother signed the paperwork to give consent to his taking the steroid orally and it ultimately saved his life.

"I got to live. That's why I want to become a doctor to help other people."

Unlike a neurosurgeon I once met who was already half way out the door before the end of my allocated five minutes with him, my chiropractor spends at least an hour with me every time because of my body's unusual responses to treatment. He never complains a bit. "This is what your body needs, and that is what we do." He reassures me every time I apologize for my being a problematic and troublesome patient. "We already know you are a troublemaker. I don't care what they say about you. I still like you," winks my beloved doctor.

What do you do? Why did you get into the field? What was your original conviction?

On the show, a nurse trainer is working on bringing kindness into the healthcare system. She recounted a personal experiences from the other side: a family member was hospitalized and she was there visiting. At regular intervals, medics come in the room to take the patient's vitals. They talk with a flat, distant voice. No eye contact with the patients or their families. They do what they need to do, and they are immediately on their way. Very transactional. A register nurse echoed the sentiment by admitting that she and her peer were trained to behave the same way. Be detached and impersonal. Kindness and compassion were not part of the equation.

"Were you trained to never cry with your patients?" the host asked. "Yes, we were. However, I cannot say that I followed that strictly." She went on to describe how one time she cried with her patient.

At the ER, a trauma patient was bleeding so extensively that, after trying for a while, the medical team decided that there was nothing more they could do to save him. One after another, they left the room. The patient, who was still conscious, gathered that the doctors had given up on him and that he was dying. "Am I dying?" he looked up to seek confirmation from this nurse. She did not answer the questions. Instead, she said, "I am here with you." Tears came down her cheeks as she held the patients hand with hers.

I told my chiropractor about the radio show. His face dropped as I got to the point about kindness being non-existent in the healthcare system. "Nope, it is not about the people. What kindness? They don't know about kindness. It's all about the money." Then I noticed my doctor was tearing up.

"Do you know that I once almost died?"

My doctor told me he had a very bad case of asthma as a child. He was hospitalized. His doctors thought he might not make it. It was 1955. Prednisone just came out. His mother signed the paperwork to give consent to his taking the steroid orally and it ultimately saved his life.

"I got to live. That's why I want to become a doctor to help other people."

Unlike a neurosurgeon I once met who was already half way out the door before the end of my allocated five minutes with him, my chiropractor spends at least an hour with me every time because of my body's unusual responses to treatment. He never complains a bit. "This is what your body needs, and that is what we do." He reassures me every time I apologize for my being a problematic and troublesome patient. "We already know you are a troublemaker. I don't care what they say about you. I still like you," winks my beloved doctor.

What do you do? Why did you get into the field? What was your original conviction?

Comments

Post a Comment